Phoenix is an “accelerated woman,” a genetic experiment who has grown to the form and capabilities of a near-forty-year-old woman by the technical age of two years old. She’s kept in Tower Seven, one of several bastions of scientific and technological research outside the realm of government oversight (but not outside the realm of its funding); these Towers are prisons for the altered humans and other biological experiments who live inside them. Phoenix, however, is destined for far more than captivity—instead, she will change the face of the world.

The Book of Phoenix stands as a prequel to Okorafor’s stunning Who Fears Death (2010), occurring before and during the technological apocalypse that makes up the extremely distant—and by that point, mythologized—past of the earlier novel. Both novels center on the tale of a powerful woman who is determined to make right the wrongs she has found in the world on both a small and grand scale. The Book of Phoenix, however, is more distinctly in a clear and wonderfully productive relation to the afrofuturist movement in the arts—its setting feels far more contemporary and is therefore more molded by contemporary class, race, and global cultural politics.

Also, where Who Fears Death read more like magical realism set in a far-flung future, with a touch of science fiction as underpinning, The Book of Phoenix is strongly science fictional (with its own elements of magic). The frame tale that opens the book is of a man named Sunuteel and his wife, living in the desert as nomads. Sunuteel finds a cache of old computers, buried away after the society of the past ended in apocalypse, and one uploads a file onto his portable: it’s the file that forms the root base of The Great Book, the religious text central to life in Who Fears Death. So, in a way, this is both far-flung prequel and much closer prequel—because though the body of the novel is about Phoenix, the closing chapters are also about Sunuteel’s construction of The Great Book and its effects on the world.

The first recording Sunuteel listens to, though, is the titular Book of Phoenix: the tale is a memory pattern lifted from one of Phoenix’s feathers, in practice an oral recount of her experiences from Tower 7 to Africa and back—up until the end of the world. Okorafor works better than almost any current writer I’m familiar with in the form of the “told-tale” or spoken narrative; I’ve noted that before, in reviewing her collection of short fiction Kabu Kabu, and it’s especially true here. Phoenix’s narrative voice is immense, compelling, and powerful. Her words ring with intentionality and strength and sharp observation—the things that together have the potential to craft an excellent story.

And an excellent story it is, really.

I tend to appreciate the density, cleverness and rhythm of Okorafor’s prose. She’s certainly an author I’m always on the lookout for, ever since I read Who Fears Death—a real powerhouse of a novel that spans genres and political concerns with seemingly effortless skill. The Book of Phoenix is a shorter and faster read, with concerns shaped more by contemporary global racial politics—in particular, the relations between America and Africa—but it, too, is a provocative book that has a deceptively transparent narrative style.

The thing I found the most compelling, though, is the complex relationship Phoenix has to the idea of being American and African, of the fraught heritage of slavery and diaspora. One of the most memorable small moments in the text, for me, was the moment in which Phoenix refuses to ever, ever set foot on a ship carrying her from Africa to America—refuses to participate in the bleak and terrible history that it implies.

And the history of colonial interactions also inform the politics of LifeGen’s corporate strategies and worldwide exploitation of resources, people, and spaces. As Phoenix devastatingly and aptly observes, the scientists and guards and supporters of the Tower projects—projects which primarily exploited the bodies and lives of African and black people more broadly—have no capability to understand that their subjects will revolt and change the world. In a fundamental way, the politics of contemporary racism are what bring about the end of the world in The Book of Phoenix. That’s a powerful and stunning realization, as we come to the end of the novel—that the message is, in part, if we do not change things we are headed for catastrophe.

This is also married to the exploitative potential of American and Western capitalism, the growth and development of technological and biological advancement without ethical frameworks, and the danger of seeing other humans as less than human—for reasons of race but also gender and class. The reason Phoenix burns the world in the end, after all, is partially to scour it of the seven impossible wealthy LifeGen investors who have used their brutal power to become nearly immortal. Greed, evil, and exploitation are all explicitly linked in this highly critical and highly emotional tale.

Which probably makes the book sound, to the sort of folks who like to detract from crunchy fiction doing hard work, like a tract of some sort. I’d challenge those folks to pick it up and read it, though—because it’s some of the most fascinating and relevant sf I’ve read in some time, too. The framing tale deals with the evolution of religion, story, and language at the hands of people who are, simply, people and products of their time. The central story deals with the complex realities of biological and technological engineering, the contemporary economic system, and the continuing exploitation of the countries and peoples of Africa by the west—while also being a compelling story of a woman’s journey to discover her genetic (and magical) powers, free her compatriots, and change the world with her gifts alongside a man she loves and a man she loves like a brother.

The Book of Phoenix isn’t just well written, and it isn’t just smart as hell; it’s also a damn good story, and it kept me reading almost nonstop all the way through. I was desperate for Phoenix to reveal the nature of the catastrophe that changed the world. When it came, I was both shocked and strangely satisfied—aware that it was the only possible righteous path for her to take. Sunuteel believes that it is because she’s a woman and women are vengeful; Sunuteel also, as we understand in the closing chapter, is a man of his time and therefore a man who interprets according to his experience. Phoenix’s power is vast and brutal and loving all alike, and her relationship to religion, life, and death is complex. So are her loves, her losses, and her choices.

Okorafor, here, has confirmed for me that she’s doing some of the most interesting work in the genre right now—and perhaps outside of it, too, combining a multinational, politically challenging, brilliant voice with the narrative expectations of science fiction and fantasy. It’s a marriage of styles and tropes that I think works delightfully well to birth something original, sharp, thoughtful and evocative. Great book, this one, and I’d strongly recommend reading (or re-reading) Who Fears Death afterwards too; the added context is very interesting.

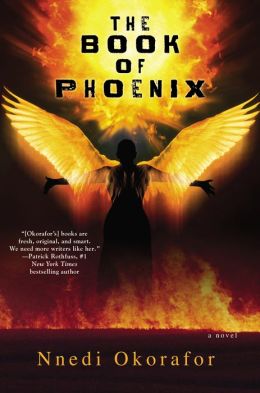

The Book of Phoenix is available now from DAW.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.